Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 53

Predawn, Falsework, Column Line 7 (Original Scan)

Left: Predawn.

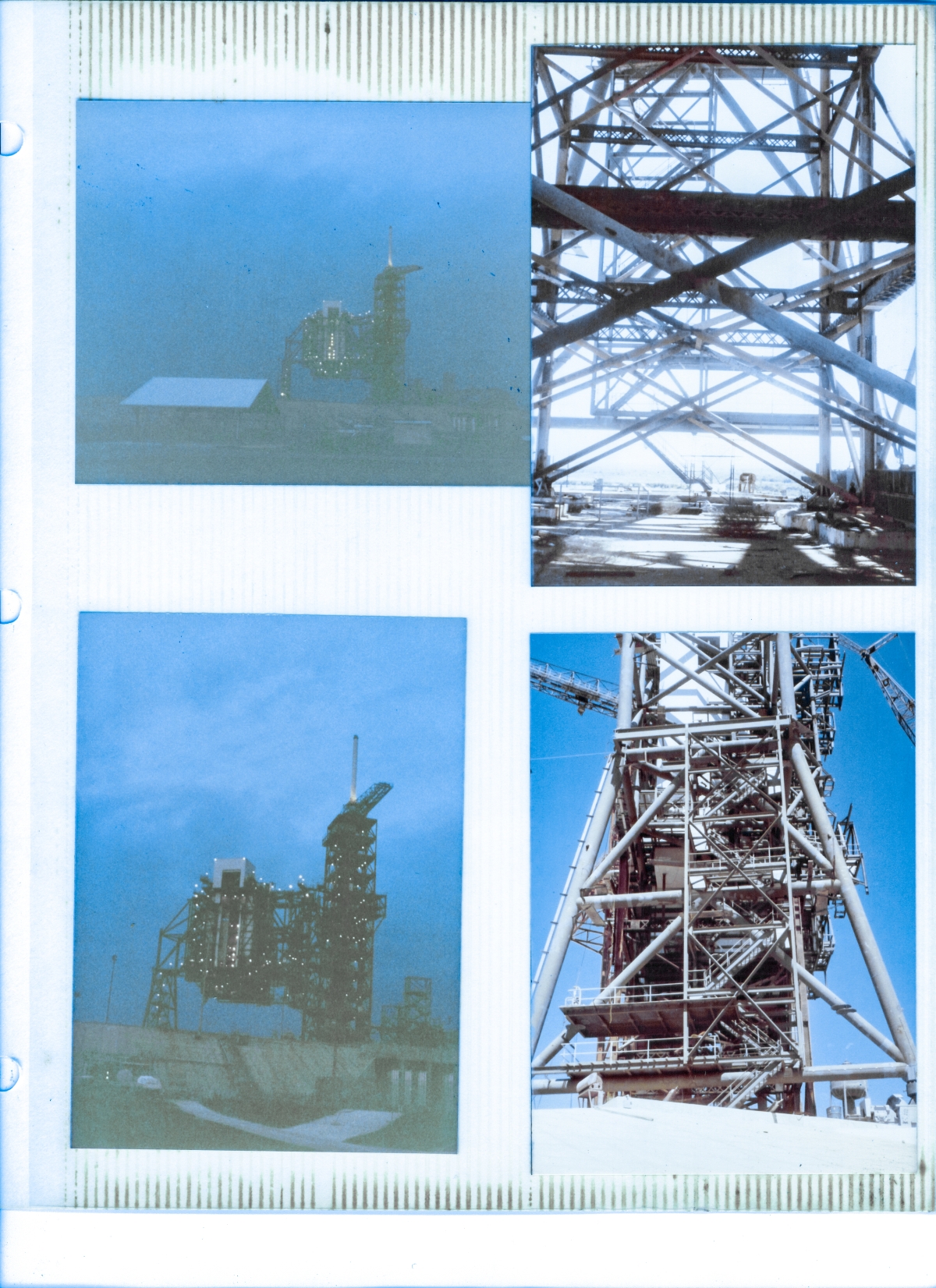

Top right: RSS Falsework, viewed from the foot of the FSS, looking toward the southwest with the RSS in the demate position, which is where it was built.

Bottom right: Column Line 7 stair tower, from a little ways down on the pad slope, looking more or less directly back in the opposite direction as the above photo. The RSS primary structure had seven column lines with the Hinge Column, closest to the FSS, as line 1, and the far side, where the drive trucks are located, being line 7, which is what you're directly facing in this image. Column Lines A, B, C, and D, ran from the back of the RSS forward, with Column Line D being the front of the RCS Room. You would find your way around on the structure, and/or locate things with high precision on drawings and paperwork, via the alphanumeric column line designations along with an elevation.

Also, this scan never had a prayer, when it comes to a workable setting for the color corrections that might be expected to do at least semi-adequate justice to all four of the included photographic prints simultaneously, so I just sort of hit some kind of middle ground with the overall scan, and then tweaked the individual photographs separately in the blow-ups of each one which follow. Still no prayer for the individual photographs themselves either, because the ambiance I was trying to capture with the pair on the left side is uncapturable, and the insane extreme highs and lows, shooting in shade, at the shaded side of a labyrinth of dark steel which is silhouetted against a brilliant sunlit sky... yeah, they tell you not to do stuff like that in Photography School, and they've got good and sufficient reasons for telling you, but of course I've never done well in structured environments where people I'm none too sure of qualification-wise, walls papered with framed certificates notwithstanding, start laying down laws that I fully intend to smash into tiny splinters at my very first opportunity to do so, and sometimes they were right, and sometimes I was right, and all times I'll be pushing things

just as hard as I can push them... because.

Non-standard sequence of images on this page. You already know all about that kind of stuff.

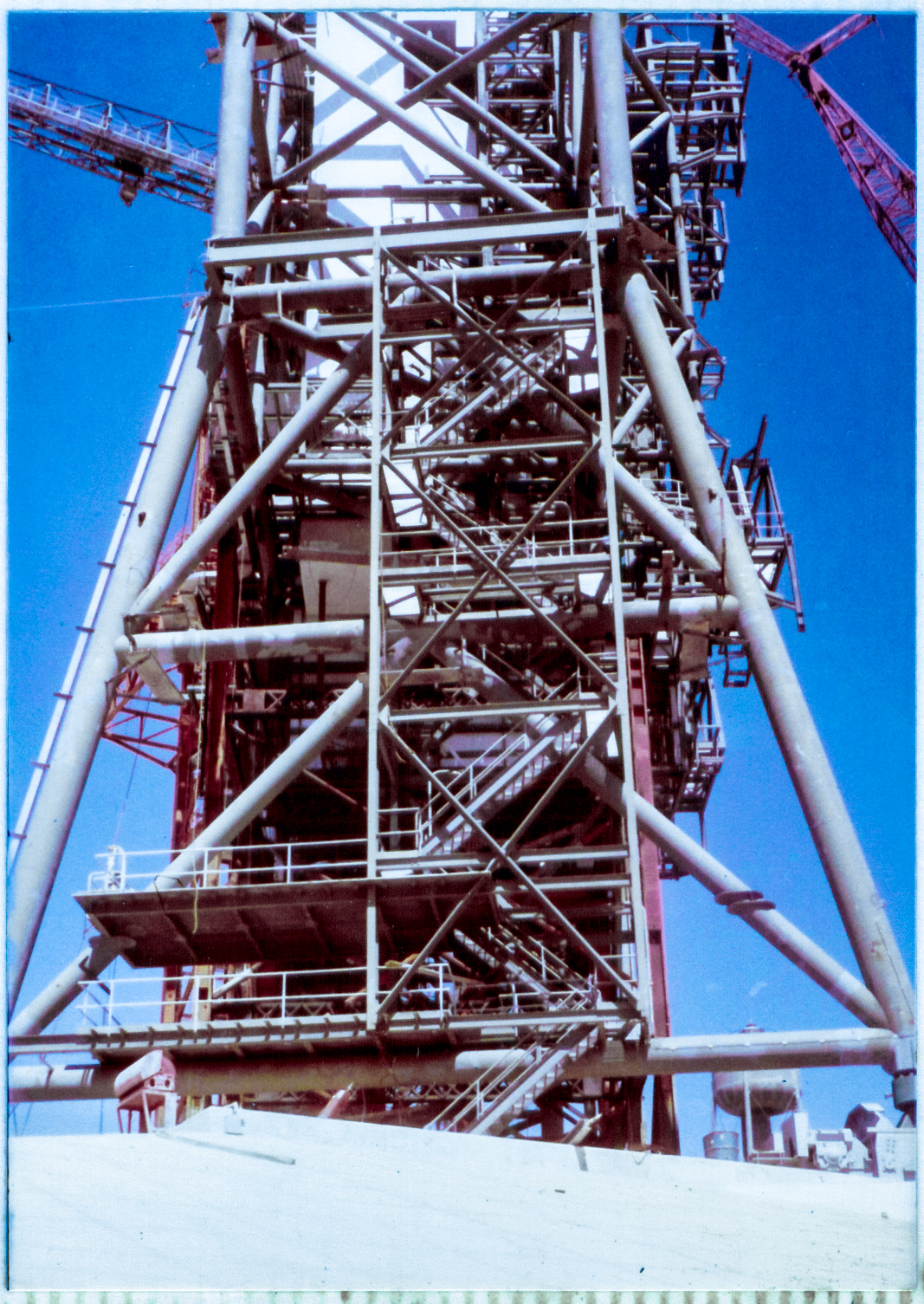

Top Right: (Full-size)

Wilhoit's Falsework.

This will be the best image, the best close-up of the falsework that they built the RSS on top of, that we're going to be getting in this series of images and stories.

Look down and to the right near ground level, where a pair of pipe diagonals meet one of the vertical members, and between the pipe diagonals you will see the shadowed silhouette of an ironworker's torso and head, viewed at an angle from behind. Kinda helps give a sense of scale to things.

I've already discussed my opinions about what I believe to be the story behind this stuff, and in this frame, you can get a better idea of the nature of all that dual-member, crosshatched with x-bracing stuff I was going on about earlier, and if you'll go back up to the top image, the one with all four photographs on it, and give it a click, it will enlarge to full-size, and the treatment of that image is different, and you can see a little bit more detail in some of the horizontal and vertical members of the falsework, in particular the largest darkest one running side-to-side roughly two-thirds up from the bottom of the frame.

Wilhoit erected the RSS on A Pad too, prior to B Pad, using the Mobile Launcher as a sort of ready-made falsework, which perforce located the growing RSS in the MATE position, spanning the flame trench, sitting on top of the Mobile Launcher with the Launch Umbilical Tower rising into the sky directly in front of it.

And I would imagine that did not work out so very well, because when it came time to do B Pad, they scrapped that whole idea, told NASA, "You can keep your Mobile Launcher thank you very much, we won't be needing it," and went straight-up from the pad deck with the falsework over at B Pad on the second go-round, building the RSS in the RETRACTED position.

I was not around for any of the Pad A work, so I have no background whatsoever on that end of things, above and beyond such fragments of information as I could glean from my boss, Dick Walls, and the Wilhoit crew, and some of the NASA types, all of who were part of that work and knew all about it.

It must have looked like a good idea on paper, but I can see where trying to put something as complex and gigantic as a fucking Rotating Service Structure together, while it was sitting over a giant steel box, that itself was sitting over a gigantic gash in the ground, could cause more than just a few problems with access to things.

So they ditched that shit when they moved over to B Pad, and went at it over nice firm flat easy-to-move-around-on-and-get-to-things, solid concrete that you could drive a crane right up next to, or even underneath, and otherwise not have to hassle with going around ridiculous gigantic steel boxes that were built like a cross between a submarine and a bomb shelter all the time, or going around ridiculous gigantic holes in the ground all the time, too.

You look at this stuff closely, and you have to start wondering about the particulars of it, and the exact, precise, structural characteristics of it, and you know that Cecil Wilhoit knew what it was good for, structurally, without even having to think about it, because he was as hands-on with this kind of stuff as they get...

But what about the guys over on the NASA side of the house?

What about all those young rosy-cheeked engineers fresh out of college who got tasked with running the calcs on this stuff?

"You're going to be using what?"

"And you know it's capable of carrying the load you intend to carry on it how?"

And the NASA managers are breathing down these poor schlub's necks, demanding complete understanding and assurance, technically, that it will hold up the whole RSS...

"...'cause ya know, we'd kind of like to make sure the damn thing doesn't collapse, killing everybody on it and under it, and disrupting the whole Space Shuttle Program in the process..."

"...so maybe try to see it from our point of view if you can, and maybe try to understand that we need to know, in the most rigorous and technical manner possible..."

And Cecil's probably already underway with it, and one of the things I gleaned from the people who worked with him, is that Cecil Wilhoit (and Red Milliken, who I did know and work with, too) were not the kind of people who would dawdle around once they had their teeth sunk into something, and I distinctly remember one of the engineers who worked the erection of the FSS on B Pad, which was also done by Wilhoit, telling me that they'd be in a meeting discussing the particulars of picking up the next two-level segment of the old LUT which the FSS was built from, and as somebody or other would drone on about this, or that, or some damn thing, deciding whether or not they should allow it, they'd be looking out the window of the field trailer watching Wilhoit's cranes in the process of lifting and setting the very segment they were talking about, and I'm pretty sure when it was time to get moving on the falsework, things were probably more than just a little bit similar, and here's the poor NASA engineers who first off have to figure out what this stuff is, in the first place (pretty sure there were no as-built drawings for whatever old bridge or abandoned factory that got taken apart to furnish the raw material that the falsework was constructed from), and what kind of shape is that material in anyway, and is it rusted, or otherwise structurally compromised in some other, possibly well-hidden way? ...and yeah, I can just imagine all the fun everybody had with that little element of things as it was going on.

Buncha damn junkyard scrap iron, and now it's holding up our nearly-finished RSS, which now weighs in the millions of pounds, and it sure would be nice if it keeps on doing that, and doesn't decide to suddenly... fail.

But Cecil knew, and that's that, and the RSS stayed right where he built it, of course.

And if you look close, at the picture of the RSS going up on A Pad, you can see that they still needed falsework, only a little less of it is all, and by golly, some of the same bridge-demo rat-hole stuff, the weirdie dual-member, crosshatched with x-bracing stuff, is in there, too, so it turns out that although the look of things is dramatically different between the two approaches to erecting the RSS on the two different pads, the actualities are not nearly so different as you might at first suppose, based on a too-quick look at the external appearances of things.

Bottom Right: (Full-size)

And then you walk out from underneath, into the brilliant daylight, hoof it southbound half-way down the pad slope over there, and then turn around and take a picture of things looking back the other way.

And the color's all goinked up on this image too, and in order to get the main meat and potatoes of the thing, the RSS, to look at least half-normal and not all weirdly dark red and orange down in the shadowed areas, you more or less just throw the red and orange components of the image away, and you wind up with something at least sort of usable, or at least it is so long as you don't look at the crane boom, 'cause the crane boom was most manifestly not a weird shade of magenta, no matter what this image is trying to tell you to the contrary.

Column Line 7.

A truly amazing thing, all by itself.

And you're staring right at it.

Aside from the Hinge Column, the two large slightly-slanted members going from the ground up near both edges of the frame are the heaviest iron in the whole tower, and weigh a very-respectable five-hundred fifty-seven pounds per running foot.

Heavy iron.

The Column Line 7 Emergency Egress Stair Tower is shown well in this frame, and you can see that they built it outboard of the rest of the structure of the RSS, and had to hang a fair-sized wide-flange beam out there past Line 7 itself, between Lines A and B, to support that side of it. Nobody ever used that stair tower for anything.

Except me, of course.

No end of spectacular wide-open views from that thing off to the south and west, and I came down off the tower going the long way around, on foot, using this stair tower instead of the FSS elevators, on numerous occasions. Between the view, and the near-complete isolation over there, it was one of my favorite places on the whole set of structures.

Going up from the left side of the top of the stair tower, you can see the white blandness of the insulated-metal paneling that enclosed the PCR Elevator and the Elevator Lobby, which had a peculiar triangular floor plan, and if you look close, near the top of it in this image, you can see that the triangularity of the lobby layout becomes apparent along its top edge.

To the right of that, past the vertical main-framing member of Line B, the latticework of the RCS Room framing steel continues to get added to by Wilhoit's crane.

Zoom in on the image, about half way up the stair tower, look at where the big pipes are going together at either either side of the frame, and you can see another way the ironworkers would make themselves temporary work areas, without floats. If you're going to be somewhere for a while, perhaps engaged in making a large full-penetration weld on some big pipes, you can just grab some 3x3x¼ angle-iron and weld it to the piece you're working on, and then lay boards across it, and you're good to go.

I distinctly remember being more than a little bit surprised and frightened when I first saw one of these setups. They very much do not look substantial in any way. The goddamned spindly-looking pieces of angle-iron just sort of stick out there, unsupported by anything, and they give a strong appearance of being... brittle, or weak, or some damn equally-unpleasant thing, and the thought of hanging your own personal ass off of a thing like that can give you a case of the shivers if you don't know how stuff like this really works.

3x3x¼ angle-iron is pretty sturdy stuff at human-scale, and when you hit it with some fillet-weld to tie it to another sensible piece of structural steel, what you wind up with is ridiculously-strong at human-scale, and can be trusted with your life and everybody else's life too. And I would suppose that it's a little like packing parachutes. You pack your own parachute, and that way you know the sonofabitch is packed right, and if you weld your own angle-iron to the structure before you put a board or two on it to sit down on and go to work, you're gonna know that's been done right too. And so that's how they do it, and nobody falls off the tower, and the only guy who doesn't like it is the idiot NASA corrosion-control "expert," 'cause my-goodness, look at what all that nasty welding you're doing has done to my precious finish-coat paint job, but fuck that guy. Nobody likes that guy anyway. And he's a chickenshit motherfucker on top of it, and you can rest assured that he's never gonna get within a country mile of where the angle-iron got welded to the structure to "inspect" it, and even if he asks to use the skipbox, the crane operator's gonna be busy that day with other much-more-important tasks, and would you please just go to hell and get it done and over with already?

Down in the lower-left end of things, just left of the apex of the pad-slope concrete, there's a little barbecue-grill-looking thing, but we're not gonna be having a barbecue out at the pad today, ok?

That thing is a camera mount, and I'm pretty sure it's this one, and it has a roll-down metal blast-cover to keep things from getting blown to hell when the Shuttle takes off.

So no barbecue, ok?

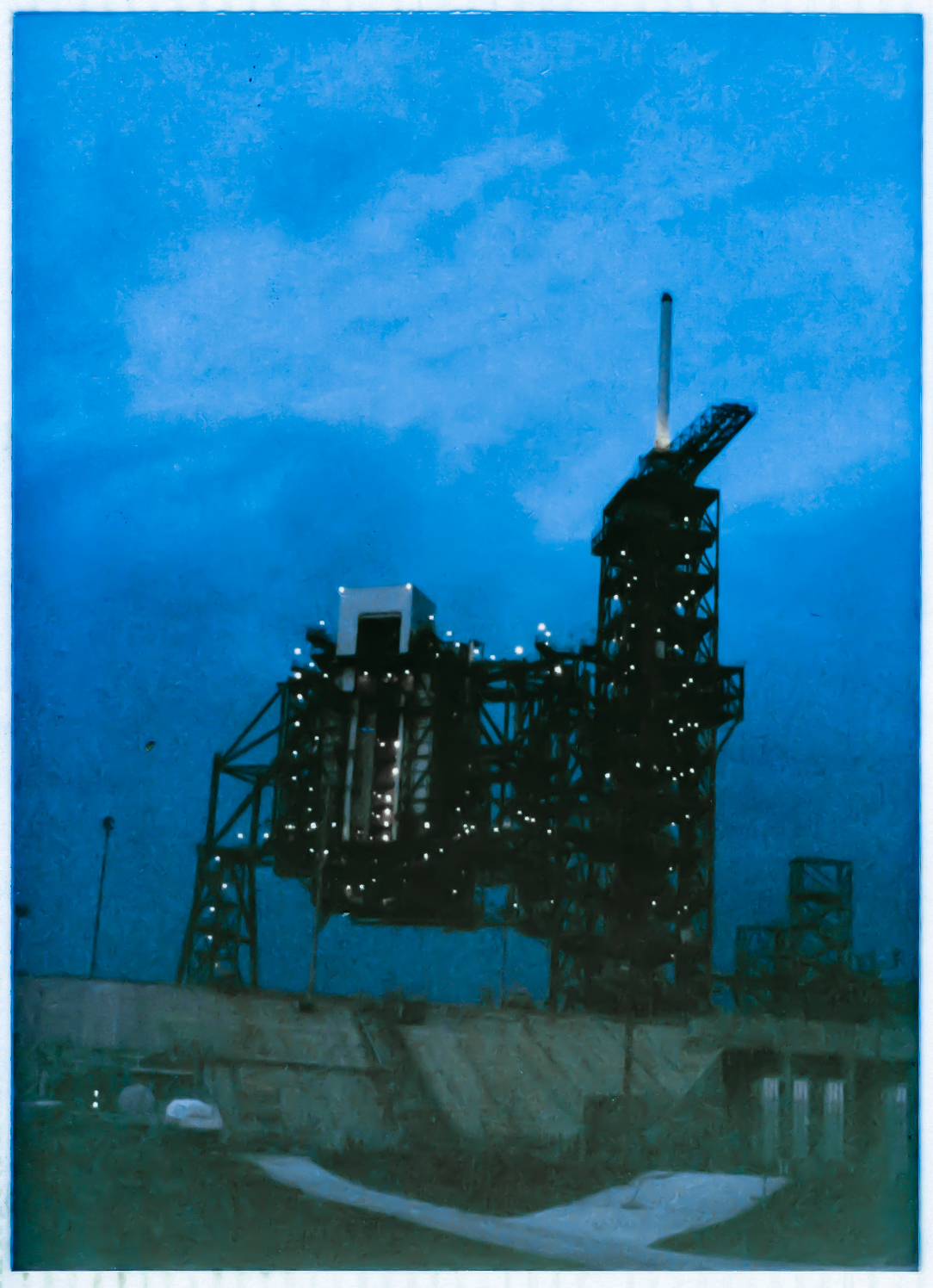

Bottom Left: (Full-size)

I already know it is impossible to describe the ambiance of this image, and the next one down below it, but I'm going to try, anyway.

The poor camera never had a chance. Common Kodak color print film, ASA 400. Even back in these days I was shooting manual for the most part, and these two frames are examples of my trying to push things farther than the system should ever have been pushed, and that includes my refusal to ever shoot with a tripod. Hand-held. Every last shot. So I had to teach myself to hold my hand and my breathing steady, and I could generally get down to around one fifteenth to one twentieth of a second and have reasonable hope of getting a sharp enough image, but then on top of that, whatever too-dark image that resulted, in situations like this where the light was still too way too low for the lowest possible shutter speed, was processed down at the Rainbow Photo (it's been many a long year and I still miss you guys) with their new-fangled one-hour color film developing machine, and the machine did what it did, taking its best guess, using the film, the chemicals, and the paper it was given... and this is one of many possible results, none of which could possibly be true, none of which could possibly be accurate.

So I already know we're looking at nothing of the sort when it comes to what my eye was apprehending this dark predawn morning, and in the case of this image, and the one that follows, I said, "Fuckit, I'm not even gonna try for fidelity, 'cause there was no fidelity in the first place."

And instead, I went for what my mind's eye is giving me, nearly four decades later, 'cause really, I trust that image more than I trust the image on the piece of chemically-treated paper that's in the photo album, and I've worked light and shadow and hue and tint and all the rest of it (but not any outright cuts or substitutions, no cut and paste bullshit with fucked-up Photoshop) with a computer, to try to bring back, if only to the tiniest degree, that mind's-eye image that I can still see, right now. I work with what I work with, and if I wanted to just make something up, I'd get out the oils and the brushes, and create something from scratch.

But that's not what we're doing with these images. Every last bit of it is renderable from a starting point which is the original scan. What's the point in lying about this stuff? It is what it is, and what it is, is some very old pictures that we're trying to breathe a little new life into, and that's all it will ever be.

And so the success shall be mine, and the failure will be mine, and I'm good with it either way.

And so we find ourselves looking at the opening scenes at the premier of Lord of the Rings Meets Bladerunner.

A great Redoubt.

A great gloom-shrouded Keep.

Set atop a high rampart, towering above the wilderness lands all around, surveying and controlling all that lies within its gaze.

Hewn of strongest steel as if by giants, a colossal and unknowable thing to defend and birth the fires of a Great Dragon which flew upon thunder, above the highest clouds to a deadly place where there is no air to breathe, the daytime sky turns black, and the stars shine at noon.

And yeah, spend enough time out here, and you'll start talking funny, too.

And the one thing this image most completely fails to convey, is the size of the thing, the scope of the thing when viewed from the moderate distance of a quarter mile.

In this image, you see a dark shape sprinkled with white specks.

That's nice.

And you cannot imagine.

It loomed in the darkness above you. It glowered down upon you. You felt it more than saw it.

It was possessed of a great dark power that emanated out from its center, holding everything all around it tightly in its grip.

If it were a mere mural it would take a building forty-stories high by two-hundred stories wide, and even then, it would be a flat lifeless thing with no depth.

Pad B had depth, and that depth held secrets, and as you came upon it in the thick and palpable gloom when stars still shown in the dark and dimly-blueing sky, you could feel this motherfucker.

And, as I said earlier, I already know it is impossible to describe the ambiance.

But I tried anyway.

And I tried to take a picture of it.

And these pitiful images are all you'll ever get, which means you'll never get anything at all.

Top Left: (Reduced)

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |